Political questions old and new

Yesterday was a day of politics. In the morning Red Sea Research called, again, doing a poll, again, on the upcoming Irish general election. Their questions were of the type "if the election were held tomorrow, how would you vote?" Considering it was Tuesday and the actual election will be on Friday, this premise didn't seem likely to offer many insights useful to the election process, especially as the poll doesn't seem to have been published yet today. Most of these surveys only interview about 1000 people across the country, so my responses constitute about 0.1% of the entire electorate supposedly represented by the poll. We can be sure I'm skewing the responses quite a bit, considering my track record of being largely out of synch with the majority of my compatriots in terms of voting behaviour over the years. The last survey I participated in a few weeks ago turned out to be for Paddy Power, the large Irish bookmaking chain – no bad thing, as frankly the betting there is a better indicator of how the voting is likely to go, compared to much of what passes for political analysis in this country.

What's really revealing about these polls is what questions are included. This one was fairly vanilla - how likely are you to vote (on a scale of 1-10 from dogged-antipathy "I definitely won't" to I-can-control-the future "Certain I will"), who did you vote for last time, who will you give your first and second preference to next time. The last poll, on the other hand, included the rather loaded question of asking how much I agreed with this statement: "Given their behaviour over the last year, I will never vote for Fianna Fáil again." There are so many things wrong with that as a survey question that it undermines the validity of the whole poll. The last one focussed quite a bit on trust, presenting the statement "I have less trust in politicians now" and also asking which coalition I'd most trust to handle the economy. The interviewers meanwhile couldn't correctly pronounce Finna Fail (no fadha, so just 'fail') or Eden Kenny (no, they couldn't get Enda's first name correct, possible future Taoiseach though he may be).

The range of possible answers also strongly shapes the type and power of the results. No simple yes or no, some questions asked you to rate your answer on a scale. Others asked you to remember and choose between five possible answers, which were along the lines of "I will definitely give my first preference to this party, irrespective of what is said before the next election," "I will probably give my first preference to this party, but I'm waiting to hear what is said before the next election," "I'm not sure who to vote for, but I'll probably give this party my first preference," "I'm not sure who to vote for, but they seem like the best choice overall," and "I definitely won't give my first preference to this party." Yet despite these types of answers being the only ones allowed, the survey results are usually presented as how many seats a party will win or what proportion of the votes they'll get.

Later in the day the political theme continued when my grandmother, now in her mid nineties, called from the nursing home where she lives to ask my advice on how to vote. This exchange happens with most of my family at some point in the lead up to an election or referendum – on at least one occasion a family member has actually phoned me from the polling station for an amusing last minute consultation before casting their vote. It's quite strange as I don't consider myself particularly politically engaged or knowledgeable. In all these situations, and particularly with my grandmother, my concern is to help her determine who she wants to vote for and help her feel comfortable with the process, and I really don't want to influence her voting decision, so it has to be handled carefully.

According to her, the nursing home staff had come in and told her that she was going to have to vote that day at 4p.m. – apparently she'd had only a couple of hours notice of this, it was three days in advance of when the rest of the country would vote on Friday, and it was before, for example, the final televised political debate that evening. One can only hope that privacy would be respected and that the same precautions against electoral fraud would be taken in the nursing home as in any other polling station. Given the scandals that have engulfed some nursing homes in Ireland in recent years – not, I should make clear, the seemingly very good one my grandmother lives in - this definitely raises concerns. My grandmother is completely compos mentis, but one also wonders what happens for the numerous residents who are no longer in full possession of their mental faculties. Do they vote? Does someone else essentially vote for them? Various aspects of this situation seem like they could undermine the political rights of nursing home residents. Definitely a process ripe for investigation.

Focussing on the task in hand, my grandmother and I went through the list of candidates in the constituency where we both live, and she decided which candidates should get her first to fifth preferences. In case anyone not steeped in Irish political process is reading this, Ireland uses a proportional representation system, so multiple preferences can be indicated and will count in determining who ultimately gets elected in our multi-seat constituencies. Each person's single transferable vote has a value well beyond just ticking the box for a single candidate.

There is a quota for each constituency – which (I think) is the total number of votes cast there divided by one more than the number of candidates, plus one vote. So in a four seat constituency with 40,000 valid votes cast, the quota would be 8,001, or 40,000 divided by 5, plus one vote. This is the minimum number of votes each candidate would have to get that would ensure that four candidates but no more than four candidates would have enough votes to be elected. If a candidate gets more first preference votes than the quota, he or she is elected, and the amount of votes over the quota are then distributed to the other candidates according to the second preferences indicated on the voting slips. So if a candidate got 8,601 votes, 600 votes would be distributed.

In practice, rather than just taking the last 600 votes counted and redistributing them (which wouldn't be necessarily representative of the overall second preferences of the people who voted for that candidate), either all of the votes or a random sample of the votes for that candidate are examined and the proportion of second preferences determined. So if say 50% of the second preferences were for another candidate in the same party, 20% for a different party, 20% for an independent candidate, and 10% had no second preference, then 50% of the 600 votes over the quota would go to the candidate in the same party, 20% to the independent, 10% would be set aside and so on. So another candidate could later get elected on the second preferences.

Another way each person's vote keeps its value is when the candidate with the least votes is eliminated during the vote count. All of that candidate's votes are then distributed according to the second preferences, where they are added to the second candidates' totals, and valued the same as a first preference vote. There is another count, and another candidate might then be over the quota and elected, or another candidate might be eliminated, leading to more redistribution of votes and further counts. This is why there are so many counts in proportional representation systems, and why it takes so long for the result to become clear.

This system also means that if you put down enough preferences your vote will contribute to electing those who actually get the seats, even if your first preference doesn't get in. Though many people don't consciously realise it, I think this aspect contributes to a greater feeling of participation, to the popularity of the system and to a slightly stronger sense that whoever is elected does in fact represent the electorate – there is less polarity. In theory, if you put down a preference for every candidate, down to your tenth or twentieth preference, you would have contributed to the election of who ultimately gets in, so you couldn't really claim that they don't represent you. Of course, lots of people will not put down any preference for some candidates, because they don't want to contribute to their election under any circumstances, so it's not the case that every elected candidate has some kind of total mandate. My grandmother decided that five preferences were quite enough, and many people would have a similar attitude. Both the system and the fact that constituencies have more than one seat have a big influence on how politics is conducted in this country, making it very different to the US or UK systems, for example. Something worth bearing in mind amid the talk of political and electoral reform that most candidates are endorsing as the election looms.

The final political piece of yesterday was watching the "leaders'" "debate" on RTE. Yes, every one of those inverted commas is intended. A few good points made by the current heads of the three most popular political parties, along with plenty of mudslinging, personal carping and talking over one another, predictably. Not much of substance was said, though some specifics were mentioned, and a number of opportunities were missed, particularly by Labour, to make their policies clearer or more convincing to the undecided voters.

What was depressing was that "social issues" were addressed for the first time at 23.06, four minutes before the end of a 90 minute debate. Two whole minutes were given over to it, in which each person responded to the presenter Miriam O'Callaghan's request to name a single social issue that they felt was important. Eamon Gilmore from Labour focussed on people with disabilities, from Fine Gael Enda Kenny, to his credit it must be admitted, said mental health including self-harm and suicide, and Michéal Martin of Fianna Fáil, after some side comments on other issues, said education. And that was it on "social justice" or any of the many social issues that are facing the country, apart from health which had been addressed at some length in its own section earlier.

There was no specific focus even on education though it was mentioned a few times during the debate. Nothing about foreign affairs, apart from some references to trade with India and China, even as revolutions are sweeping the Arab world and have toppled governments in the last month. The economy was discussed ad nauseam but very little mention of poverty and virtually none of inequality. There was no discussion of abuse in its many forms which have so damaged Ireland's people, nor were human rights really discussed, while climate change got an occasional nod, usually in reference to pursuing jobs in renewable energy and the green economy.

As with the whole election campaign so far, no mention of the Corrib gas deal with Shell, its potential €420 billion value, or of the possibility of renegotiating it, along with (and probably easier than) renegotiating the EU/IMF loan. Similarly no mention of the M3 motorway, Tara, Lismullin or the destruction of national monuments generally. Remember when we used to care about that stuff? Now it's just the banks, NAMA and pensions, all the time, to the exclusion of everything else.

There were a number of references during the debate to this election being the most important in the history of the state, although why exactly that should be has never been explained satisfactorily. Partially this importance seems to be attached to the possibility of a different party getting in than the one that has been in power for 14 years, though a change of government should be a possibility in any fair election, and it doesn't mean much unless they enact different policies.

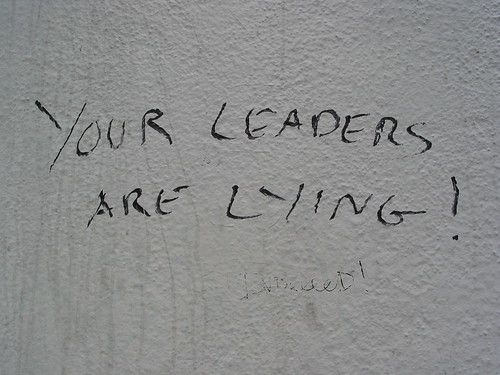

I hope this election will lead to real change for the better – with much stronger assistance to those who are truly suffering in our society, and with real reform and determined efforts to create a better Ireland. The graffiti pictured above seemed a fitting illustration and a sentiment worth remembering on this day filled with politics. I just hope that the idea of the graffiti below, first put up in advance of the second Lisbon vote and still in situ today, doesn't reflect the value of the Irish people voting this time around.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home